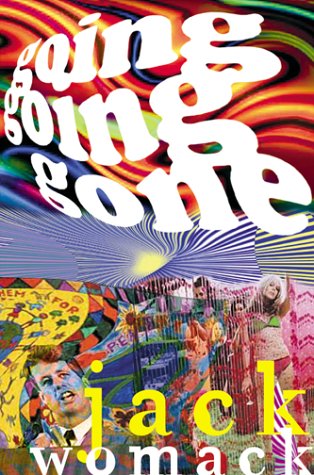

The opening of Jack Womack’s Going Going Gone, injects us into an unpredictable world that wobbles between an alternate hipster-scene of New York City in the 1960s and the seemingly hallucinatory ramblings of a drug-addled protagonist, Walter Bullitt.

The story begins in a Washington, D.C. hotel room, where the first person jive talk kicks in: “Soon as I spiked I turned my eyes inside. Setting old snakehead on cruise control always pleases, no matter how quick the trip.”

Sprinkled through almost every sentence are hokey metaphors. The phone doesn’t ring, “those jingle bells“ do. And on the other end of the line is a Federal agent of some kind, who is so square that he can’t understand a word of the hipster-narrator. But the narrator is more like one of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers than a secret agent, and he himself was so startled by the phone that he almost made for the john to “drown his bagged cat.” To flush his pot down the toilet, get it?

The whole scene is quickly shown to be a parody, but of what exactly, it is hard to say. Ostensibly we could see this as a science-fiction drug novel, like a pastiche of Ron Goulart and Hunter S. Thompson. But the language is so consistently broken, the reader has to be a lover of puns and hyperbolic nonsense to really appreciate it. Walter doesn’t sleep off his dose, he “cools on his slab until roostertime.” He doesn’t walk downstairs to the street, but “ankles hellwards,” or something like that, the verbs always getting switched up like knuckleballs that begin to seem more and more like a series of wild pitches.

Another hitch to this novel is that the drug lingo is so exaggerated and absurd. When Walter is interrogated by a pair of beautiful yet strange women who have picked him up at a live music venue, he tries to explain his constant use of drugs: “Business class tickets out of bittersville. Mind masters only, got a cold war going on with the body breakers. Can’t stand cokey joes, speedsters, redheads…“ So which drugs does he take? “Psychedelics. LSD-25, 34, 65. Mescaline and or peyote, fly agaric, ergine, ibogaine, yage, psilocibin derivative and the natural state, virola, so forth and so on.“

The inclusion of ibogaine, of course, is a great touch! The drug that Muskie was supposedly getting from a mysterious Brazilian doctor during the 1972 Presidential election campaign. Once that baby turned up, I was onto the beat of Womack’s strange thread! It is a slipstream fantasy story. Because Hunter S. Thompson made up that rumor about ibogaine in the first place, but it was three or four years after the setting of Womack’s story.

Increasingly as the tale continues, the timeline begins to get stretched or warped in ways that make no sense. Events of the late 1950s or the mid-1970s are mixed and matched into the story, artfully enough, so that when the assassination of the President is described — in Going Going Gone it is Richard Nixon (not J.F.K) who gets shot — the tapestry of events is fully revealed as a completely crazy quilt. They are not in Dallas, but New Orleans. They are not riding in a Lincoln limosine, but in a Pierce Arrow.

“Ka-chow! sneezes the roscoe. Before the Trickster feels that warm gulf breeze where the top of his head used to be he finds himself heading way down south, getting the purple-ass treatment from Satan’s snickering imps.“

Eventually even the purple prose (looks cool in black-light!) begins to have an addictive flavor to it. When some seriously weird things begin to happen, the chemically altered states of consciousness that Womack has been kicking around like an old soccer ball finally gel into captivating imagery. The way in which the paint peels off the houses and floats up into the sky during the climax of the book is rather interestingly done…and it doesn’t matter if it came straight out of a Hollywood flick. Surprisingly enough, after world-hopping and dimensions of space-time melting, the ending of the book is almost satisfying. This despite the plot holes, (so big you could drive a galaxy through them,) and the often meandering blobbergosh that the narrator is laying on us. As the action proceeds, Womack falls into a more standard prose style, so that the last fifth of the book is written in an almost ‘normal’ voice.

But hang onto your paisley bell-bottoms, brothers! If you read Going Going Gone you will have to ride the whirlwind with a monkey on your back, and if you pass the acid test, the only thing you will gain is to know how fast you can macheté your way through jungles of finger-snapping lunacy. Which is a pink and peppermint sort of trip, if you can dig it!