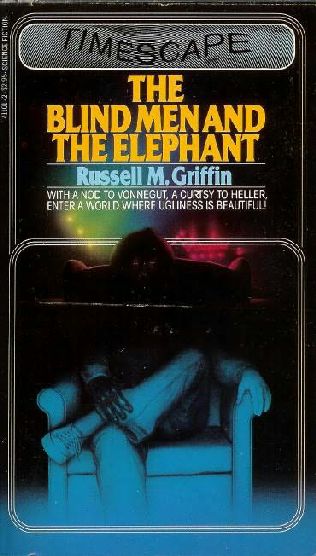

A review of The Blind Men and the Elephant by Russell M. Griffin

You would think that a novel investigating the inner life of a freak — indeed, the freak of freaks: Elephant Man — would be grim, depressing, and bleak. You would think that the transformation of one’s body into something hideous and grotesque as a terrible ordeal. Moreover the psychological pressure of being an actual monster in physical form should be a topic almost unbearable to explore. And yet, in this novel, The Blind Men and the Elephant, Russell M. Griffin explores all of these difficult ideas and emotions, he pokes them with needles and rubs salt on them over and over again… but strangely enough, he achieves an ethereal, almost philosophical understanding of the subject in the end, and instead of weeping with saccharine sympathy the reader is left pondering moral issues, and laughing bitterly at human weakness.

It helps that the book is framed as a social commentary and a bitter satire on the hopeless losers of the small town, Butler, Massachusetts. The protagonist Durwood Leffingwell is a washed up weatherman at a low budget local t.v. station, who smokes dope with the cameraman, and watches with seeming disinterest as his marriage deteriorates. The cheapness and selfishness of the cast of characters is obvious from the opening lines, evoked with deft jabs and devastating clarity.

The raw comedy of this book is demonstrated in the first glimpse of Leffingwell’s job, when he is rousted out of bed to answer a phone call from his boss, Trammel, down at the t.v. station:

“I’m trying to cope. Cope with a little prob we’ve got down on this end.”

Leffingwell took a deep breath and let go of his day off. “Shoot.”

“It’s about our live coverage of the parade today.”

“Just about to tune in and watch,” Leffingwell lied.

“You know it’s the biggest thing we’ve done. We’ve got thousands tied up in telephone line rental and the remote van and the pro switchers from Boston… I mean, Leffingwell, this is a live remote! This is the big time! This is like ABC doing the Olympics!” Trammel paused, letting the grandeur of it sink in. “That’s why I was just sick when I got the call from St. Joe’s just now.”

“The hospital? Oberon didn’t slash her wrists again, did she?

“No, it’s Tanker Hackett. He’s in traction.”

“Traction?”

“They totaled Curt’s VW Rabbit.”

“Curt too? Is he all right?”

“Yeah, but his Private Cusp suit’s just a lot of fiberglass tooth crumbs all over Route 111-A. Leffingwell, Sergeant Smile and Private Cusp were supposed to attract kiddie viewers. We’ve got no moppet interest. WE’RE ABOUT TO SEE THREE THOUSAND DOLLARS GO DOWN THE TUBE!”

Leffingwell was silent, suspecting where Trammel was headed. Ever since Leffingwell’s promotion to weatherman on the Ten O’Clock News, he’d been supplementing his $97.50 a week take-home by helping out on Sergeant Smile and the Tooth Brigade as the mute end of the many-toothed Mr. Laffy the Horse.

And it all just gets worse from there. Each line, which seems like a throw-away gag, actually gets tied into the plot during the course of the book. Griffin manages to escoriate the whole of American society, revealing it’s raw World Weekly News-fed underbelly.

In the course of the book, Leffingwell gets involved with the Elephant Man, picking up from the freak show pimp who dumped him unceremoniously in Butler, Mass, and plays out his own greed and cynicism against a back-drop of grasping locals, corrupt judges, self-promoting minor poets, and the various phony personalities of the t.v. station.

There are deep moments of self-reflection from the Elephant Man, who is utterly disconnected with human society, and who painfully reconstructs his past, trying to understand his origins and the meaning for his life on earth.

The facetious musings of a theologian, and the intrusion of mysterious pursuers wearing sunglasses, point to a horrible truth which is revealed to all eventually. What makes this novel significant, and not just a slap-stick comedy, is the way in which each of the characters hides and attempts to reconstruct their understanding of what the Elephant Man really is.

For the theologian, the Virgin birth (which is simultaneously a miracle and an abomination) is too much for his mind to handle and he snaps. For Leffingwell, the truth becomes a moral question of whether he will continue to hurt and exploit someone who has done him no harm. And for Mother Superior, what good does it do to finally know with certainty that the one child who needed her the most was the one she abandoned? As she wanders through the wreckage of her life’s work, who was saved? Was anyone really even helped?

As for the Elephant Man himself, the truth and catharsis it brings is just another punishment, like Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows he is left walking in the surf and turning around to face the emptiness of a Universe without meaning or mercy.

In the Elephant Man’s case, he is not on the beach, but in a parking lot after having been acquitted of a false charge in court. But his regained freedom is too little and too late to save him from the reality of his own Being.

Even Leffingwell, who discovers his own compassion too late in the game, only succeeds in raising his protest to the level of being a nuisance to the powers that be. With his memory erased, and all the knowing parties either dead, missing, or gone mad, there is no epitaph for the Elephant Man’s true nature.

You’d think all of this is terribly sad, but strangely enough you will spend more time roaring with laughter at this book, then you will stifling back tears. One drawback, which I should mention, is that the women in the book are generally grasping, selfish, and confused, and seem to randomly focus their affections on men in the story with a sense of pointlessness and low self esteem. You could fault Griffin on this, and say it is somewhat sexist. On the other hand, if you look at the whole story, in my view, the male characters are equally self-centered, empty, and blinded by egotism. I think it is an equal opportunity castigation of American society.

There are moments in the plot where humanity shines through, which is why I would recommend it. When Leffingwell has mindlessly set up a porno film production involving the Elephant Man as a million dollar idea it is perfectly reflected by the cameraman Stackpole who realizes with disgust what is going on.

“Leff, my man,” said Stackpole, “I just cut myself out.” He handed Leffingwell the massive camera. “You do anything you want to from here on, but you do it without me.”

“But why, Stackpole?” Leffingwell said feverishly.

“Why? It’s inhuman,” Stackpole said. “The road back to the human race is through this door.”

Leffingwell was suddenly alone, the heavy camera tugging at his arm. His face burned. He hated himself.

And in these moments of realization, in the midst of wicked satire, this book proves itself worthy of the title.